On the origins of the Egyptian Pantheon

Results of a 4WD-trip to Gebel Uweinat and to the Gilf Kebir

12/1/2009 – 12/20/2009

- part one -

by

Carlo Bergmann

1. Introduction

In the course of their November 2008 Western Desert expedition Miroslav Barta, Professor of Egyptology at Charles University, Prague, and his team paid a visit to the Wadi Sura area of the Gilf Kebir, paying particular attention to the Cave of the Swimmers (WG 52; Andras Zboray classification) and the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave (Grotta Foggini; WG 21; Andras Zboray classification) which were top priorities on their agenda. At the latter site, like most of those before him, Barta was startled by the beauty and splendor of the largely cryptic rock art that embellishes the slightly concave rounded shelter and made an important discovery, when to his great surprise, he realized that some of the cave’s enigmatic paintings portrayed gods and goddesses from the Pharaonic pantheon. Consequently he concluded that ancient Egyptian mythological concepts were primordially linked to the Neolithic rock art of Egypt’s Western Desert, notably to the Gilf Kebir.

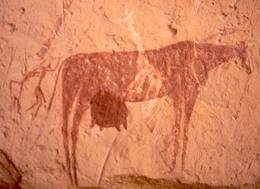

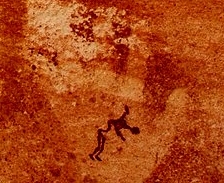

The Foggini-Mestekawi Cave (WG 21) was discovered in 2002 by the Italian desert enthusiast Massimo Foggini and his tour operator Ahmed El-Mestekawi. Although unilaterally renamed as Cave of the Beasts (“Grotte des Be´tes”; J. Le Quellec, P. and P. de Flers: Peintures et gravures d´ avant les pharaons du Sahara au Nil, Seleb 2005 ) by the prehistorian and prominent specialist in African rock art, Le Quellec et al., we shall adhere to its original name which was already consolidated into common usage long before the Frenchman, who had no involvement in the find, arrived there. The Cave of the Swimmers (WG 52) lying only 10 kilometres distant was discovered by the Hungarian explorer Count Laszlo Almasy in October 1933. Its name alludes to the notion that several small figures depicted on its walls vaguely recall humans in a floating or swimming posture. (figure 1)

figure 1: small human figures in swimming posture

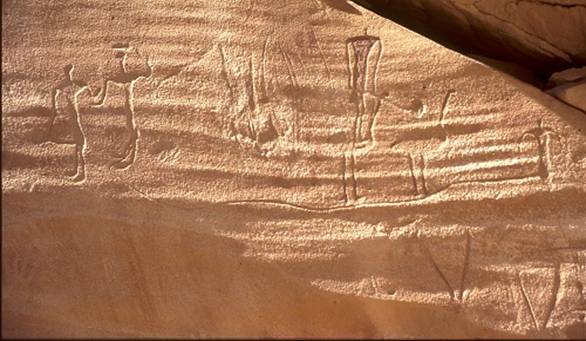

2. Attempts to date the Wadi Sura rock art

Whilst Le Quellec tentatively dated the Wadi Sura rock art to around 4,500 +/- 500 years BC. (J.-L. Le Quellec, Une nouvelle approche des rapports Nil-Sahara d´apres lárt rupestre. Archeo-Nil 15 (2005) p. 73), Barta had assumed an age ranging between “…the Sixth – Fourth millennia B. C., and most likely to the period between 4,300–3,300 B.C…” (M. Barta: The origins of the goddess Nut and the predecessors of ancient Egyptian kings. Unpublished manuscript, received on 2/26/2010, p. 2), the latter time span being considered as the period of most intensive habitation in the Gilf Kebir and the surrounding area. (J. Linstaedter: Rocky islands within oceans of sand – archaeology of the Jebel Owenat/Gilf kebir region, eastern Sahara, in: O. Bubenzer, A. Bolten, F. Darius (eds.): Atlas of cultural and environmental change in arid Africa. Cologne 2007, 36 et seq. Note that for Neolithic sites in the Gilf Kebir Hoffmann suggests a period of habitation ranging from 6,000 to probably 4,000 B.C.. M. A. Hoffmann: Egypt before the pharaohs. London, Melbourne, Henley 1984, p. 232) However, as images of giraffes present in both caves (figure 2) point to an earlier era, Barta deviating from his original proposal, reasoned that the rock art in question “… must date to a wet period in the region as giraffes need rich water reservoirs. This wet period ended around 6,200 B.C. after which this mammal had to withdraw to the south.” (M. Barta: Origins, op. cit. p. 2) Thus, according to Barta, an earlier date seems to be more likely. (Ibidem, p. 2 ) Extending the time interval defined above, he finally concluded that the period of origin of the Wadi Sura rock art probably lay somewhere between circa 7,500 and 3,200 BC. (Ibidem, p. 2 )

figure 2: altar-cave (WG 61; Andras Zboray classification): a giraffe superimposed on a cow

So, various periods have been suggested: 7,500 B.C., 6,000 B.C, 4,500 B.C., 4,000 BC, 3,200 B.C. or even later? As is evident from the different styles and manifold superimpositions, the Wadi Sura rock art would seem to have been “… created in several, chronologically different phases.” (M. Barta,: Swimmers in the Sand. Unpublished manuscript, received on 3/10/2010, p. 12)

3. Wadi Sura – a Mecca for pilgrims from the Nile?

(see P. and P. de Flers, J. J. Le Quellec: Prehistoric swimmers in the Sahara. http//rupestres.perso.neuf.fr./page 76/assets/AC_, p. 61)

Wadi Sura lies on the route of the ancient Kufra Trail and its side paths. (see “The Kufra trail – another pharaonic period road to the southwest” on this website; in preparation). This long distance donkey road was in use until 2,000 B.C. Although less probable, it may be that the religious concepts so evidently displayed in the Wadi Sura rock art, were brought there by Nile valley travellers on their way from Dakhla oasis to the west. Given the chaos of styles and motifs, we cannot say more than this about the possible age of some of the rock paintings. The only hope to establish a more precise date “… is future archaeological research in their vicinity, especially in the case of (WG 21) which has never been properly surveyed.” (M. Barta,: Origins. op. cit., p. 2)

4. Research strategy

Bearing in mind my modest resources, how could the issues raised by Barta´s discovery be thoroughly investigated? What was the function of the two caves? Were they merely art-embellished sites decorated for art’s sake only? Or were they gathering places for rituals as suggested by the inherently religious nature of the ideas displayed on their rock faces and by the sacrificial altar found at WG 61? According to Assmann, Egyptian cult rituals are “…rooted in the basic concept of a deity as resident in a locale; (they are ) not directed toward a distant divinity who must be summoned, but rather to one who is present and resident.” (J. Assmann, The search for god in ancient Egypt. Ithaca, London 2001, p. 48) Does WG 21 and its divine rock art qualify for such a place of worship? Where can one find sound evidence for such a proposition? How could datable elements in the material culture of the region’s prehistoric populations be identified? Since the 1930´s, this expanse of great natural beauty has been frequented by a vast number of tourists and also by a few Egyptologists, archaeologists, pre-historians and rock art specialists. Apart from the rock art itself, was there any chance finding anything in situ? Could the age of the rock paintings be revealed without destroying them? Determined to find answers to these questions, in the Spring 2009 I began to look out for participants to join me on this difficult venture.

In two successive expeditions, one in December 2009 and the other in January 2010, a bunch of desert addicts and myself (Uwe George, Uwe Karstens, Dominik Stehle, Christian Kny, Christian Philipp, all five of whom generously sponsored the project, and Roland Keller), hopped into 4WDs and headed together with Khaled Khalifa and his staff (Muhamed Khalifa, Ibrahim Muhamed Imam, Muhamed Abd el-Faraq, Muhamed el-Said) towards the destination of my dreams.

5. 1st 4WD-trip (12/1/2009 – 12/20/2009

5.1 Resuming an earlier cancelled project

Memories awakened in me as we embarked on our first journey into the Land of Seth were, during the past 29 years I had left behind so many footprints. In the winter of 2002/3 Heino Wiederhold and myself had tried in vain to reach Almasy´s Cave of the Swimmers from Dakhla by camel. We managed to arrive at the top of the western escarpment of the Gilf Kebir only a stone’s throw away from the famous site, in the evening of the 1/21/2003 after a strenuous hike but shortage of water brought our lives to the brink of the abyss and in order to save ourselves, we were compelled, after only a few hours sleep at that spot, to commence the forced march back to Dakhla oasis together with our camels Amur, Maqfi and Rashid. Now, at long last, it was possible to resume the survey which had been deferred for almost seven years.

5.2 An unexpected discovery in Karkur Talh/Gebel Uweinat

Coming from Gebel Uweinat, the huge pluton which, together with its neighbouring mountains, Kissu and Arkenu, mark the direction of the drift of the African continental shelf during a distant geological epoch, we approached Wadi Sura from the south. In Karkur Talh I had bothered my companions with an (in their opinion) abstruse urge to identify mythological and religious traits in the Gebel Uweinat rock art (such as depictions of ithyphallic human figures or hand prints) that could be linked with ancient Egyptian religion. This aspiration unexpectedly yielded a result when Uwe George discovered a sandstone penis, measuring 2.30 metres in length. (figure 3) Sculptures are extremely rare in the Western Desert and to the best of my knowledge, apart from a large, carefully worked 2.5 ton sandstone block resembling a cow which was unearthed at Nabta Playa, this penis is the only other Neolithic sculpture found there so far. The phallus is comprised of two testicles (figure 4) and a clearly articulated glans. (figure 5) It’s form and size suggests it had been utilized for ritual purposes.

figure 3: sandstone sculpture of a penis discovered by Uwe George figure 4: close up of the testicles

figure 5: close up: clearly articulated glans figure 6: rock art found next to the phallus (detail)

The surface of the penis shows that it had been dressed by tools. It was found next to a horizontal row of inconspicuous engravings on a narrow rock terrace overlooking Karkur Talh. The event depicted in these engravings, shown in figure 6, may commemorate a group of humans being put to flight. Does this give a clue to the sculpture’s function? Even if one considers, that for the most part, the item might be naturally shaped, the fact that it bears anthropogenic marks indicates that it had attracted someone’s attention and thus, it must have possessed an important meaning of some kind. Was it the intention of the sculptors to erect the penis in an up-right position? In this case, would the object have to be considered as a megalithic monument intended to demonstrate virility and power according to the beliefs of an obscure cult? As the period when it was used certainly goes back to “… dimly distant prehistoric times which may lie forever beyond our grasp in terms of any full degree of understanding.” (R.H. Wilkinson, The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt, Cairo 2006, p. 10) a reasonable satisfactory answer is not easy to find.

Nevertheless, we tried to find similar megalithic sculptures down in the Karkur Talh but only managed to spot one piece of rock art in which the unexplained and mysterious depiction of erect penises(?) is again in evidence. (figure 7) Revisiting a small rock shelter, in front of which I had camped with my camels 23 years ago (see picture 10 of “The road to Yam and Tekhebet – part one”, in: Results of the winter 2008/9 4WD trip to Gebel Uweinat; on this website), I cast a glance into the dimly lit interior and looked once more at the single inconspicuous piece of rock art showing a man with erect penis standing behind a quadruped; the glans of his member obviously bulging somewhat. (figure 8) From our brief survey of the vast number of anthropomorphic depictions in Karkur Talh, we concluded that phallic symbolism is relatively rare in the wadi.

figure 7: three dancers, two with erect penises(?) and knees bent (courtesy of Dominik Stehle)

figure 8: man with erect penis behind quadruped (colour enhanced for improved contrast)

5.3 Foggini-Mestekawi Cave/Gilf Kebir (WG 21; Andras Zboray classification)

5.31 A triad of nameless (Wadi Sura) deities evolving into a tetrad

When we arrived at WG 21, the enigmatic arrangement of those images engraved into the left freeze above the bulk of the rock paintings immediately attracted my attention. It consists of four human or divine figures, two of them outfitted with naturalistically shaped penises similar to the one shown in figure 8, two ostriches, two vulvae and a few negative hand prints. As shown in figure 9, the human figure slightly to the right of the centre is superimposed on an ostrich and also on the leg of a barely visible quadruped (the human figure thus probably being of younger age). This figure and the faint negative handprints immediately surrounding it, bear traces of reddish brown colour.

figure 9: nativity scene composed of two gods and a goddess, an umbilical cord, two ostriches and two pubic triangles.

Although the scene cannot be entirely explained, an attempt is made to unveil its possible meaning: The two human or, more generally speaking, the two anthropoid figures to the left of the picture, seem to represent a male holding his oversized penis with his right hand and a female of prominent status. The determinative-like, horizontal stroke or rectangle above the female’s head may be an indicator of this status but is so far uncorroborated. Linear strokes have been related to “owner’s marks”, “potter’s signatures”, “notational signs” etc. (M. A. Hoffmann: op. cit. p. 294; K. A. Bard: Origins of Egyptian writing, in: The followers of Horus. Studies dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffmann. R. Friedman, B. Barich (eds.), Oxford 1992, p. 299; E. D´Amicone: The art of vessel production. Turin 2001, p. 25). One, two or three horizontal strokes are common below the Horus names of the early Egyptian rulers (G. Dreyer: Um el-Qaab. Nachuntersuchungen im frühzeitlichen Königsfriedhof. 3./4. Vorbericht. MDAIK 46 (1990) p. 58 et seq.; G. Dreyer: Umm el-Qaab I. Mainz 1998, p. 89; http://xoomer.alice.it//francescoraf/hesyra/Dyn0serekhs.htm, F. Raffaele: Dynasty 0 “Serekhs”. Late predynastic Egyptian royal names) and occasionally, on jars (W.M.F. Petrie, J. E. Quibell: Naqada and Ballas, London 1896, pl. LIV; E. C. M. van den Brink: Corpus and numerical evaluation of the “Thinite” potmarks, in: The followers of Horus. op. cit., pp. 278, 288, 291, 293, 295; The international potmark workshop, http://www.potmark-egypt.com/Signs.asp?basic_sign-81. Note that the quality of oil was indicated by a horizontal stroke on jars found by Dreyer et al. at Umm el Qaab. G. Dreyer, U. Hartung, T. Hikade, E. C. Köhler, V. Müller, F. Pumpenmeier: Umm el-Qaab, Ergänzungen, MDAIK 54, p. 140) and Clayton rings (figure 10).

figure 10: pot mark on a Clayton ring deposited at a way station on the Kufra Trail

The stroke’s possible function as an indicator of the figure’s female gender seems unlikely, as an umbilical cord emerging from between figure’s legs (that is, from the womb; figure 11) and fusing with a “child” engraved on the far right, already supplies sufficient proof of gender. If one interprets the meaning of the determinative-like rectangle or stroke above the head of the female figure as an accentuation of her elevated position then, on that score, the figure may be seen as the consort of a chieftain who is depicted to the left of her or as a goddess who a.) has just given birth or b.) is related by lineage to the figure (her and her divine husband’s child) on the right.

figure 11: nativity scene – a god and his divine consort (detail of figure 9; colour enhanced for improved contrast)

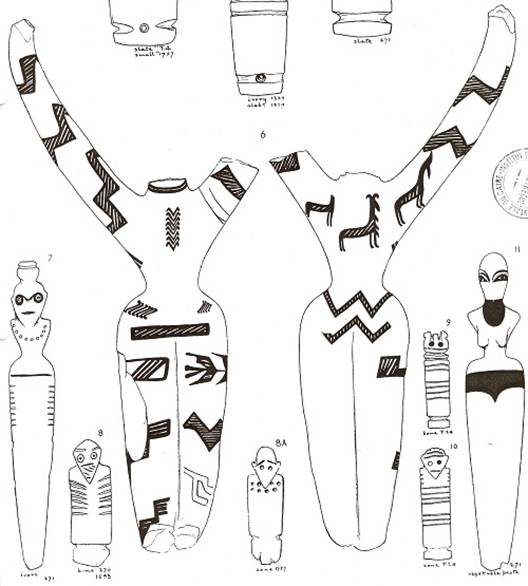

A painted female statuette found by Flinders Petrie and James Quibell at Naqada (W.M.F. Petrie, J. E. Quibell: op. cit. pl. LIX¸; figure 12) seems to suggest the divine nature of the female figure seen in figure 11. (Even though Petrie and Quibble have assigned such female figurines, tattooed or painted, to their “New Race” which they related to “…a slender European type…” (Ibidem, p. 34) or alternatively, to the “.. slave women of the previous steatopygous race…” (W.M.F. Petrie: Prehistoric Egypt. London 1920, p. 47, Pl. VI), Fekri Hassan ventures further and proposes their mythological association with early predynastic female deities. (F. A. Hassan, Primeval goddess to divine king. The mythogenesis of power in the early Egyptian state, in: Followers of Horus. op. cit., p. 313 et seq.) With regard to a similar figure he states: “Although other interpretations are possible, the female may be identified with a deity, perhaps the goddess Hathor or Bat.” (Ibidem, p. 315))

figure 12: Human figures found by W.M.F. Petrie at Naqada

Note that the two tall statuettes in figure 12 show signs “…linking the breasts and hips with water, grain, and plant symbols.“ (Ibidem, p. 314) Note that in addition to zigzagging water lines painted on her arms and legs, the figurine on the left is decorated with a horizontal rectangle at waist level in the region of the vulva whereas, the statuette on the right is decorated with zigzag water signs at the same body section. In many cultures women are frequently associated with water. “Water is connected… metaphorically with menstrual blood. The link between women and water is indicated in Predynastic iconography by the association of female figures with the sign for water and by the association with water shells (including cowries).” (Ibidem, pp. 314 et seq.) Because of its positioning and because of it being just a different representation of water, the enigmatic rectangle evokes associations related to reproduction or to female fertility. Note that the lines inside the rectangle (as seen from top to bottom) slope right to left. Later in the Pharaonic script, a lake, the sea or “ornamental water” were represented inter alia by, a hieroglyph consisting of a horizontal rectangle in the centre of which, a double line sloping in the opposite direction, is depicted. (see E. A. W. Budge, An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary, vol. 1, New York 1978, p. CXXVi, No. 66) In the case of the slim female goddess depicted on the rock face at WG 21 it seems only logical that, because of the narrowness of her torso, the said horizontal stroke or rectangle could not be placed in the region of her pubic triangle, so it was put above her head instead. However, even at the chosen place directly above the goddess, the small dimensions of the composition and the grainy nature of the sandstone, precluded the creation of a “rectangle in outline” by the method of incising two tiny pairs of vertical and horizontal lines because the horizontal lines at such small scale could not be cut into the rock so close together without removing the sandstone in between them, thus a single thick stroke was formed. The small dimensions of the rectangle also prevented the insertion of any zigzag water signs into the tiny triangle (Note that the WB 21 rock art does not feature zigzag water signs.), and any such attempt by the artist would also have fragmented the rectangle by the blows of his tools. Thus, at the given scale, it seems that there was no alternative other than to use a simplified variant of the sign as seen in figure 12, in the form of a broad horizontal stroke (a bar which, without elaborate discussion, some observers may instantly view as a rectangle in bas-relief).

When one has advanced to this point, it would come as no surprise that two ostriches are found positioned on the umbilical cord. The following quote may provide an interpretation: “Females are also associated since the Late Palaeolithic with the sky and birds…. Representations of a female figure with raised arms in association with boats, sycamore fig trees, and ostriches are documented for several Gerzean (late Predynastic, Naqada II) pots.” (Ibidem, p. 315) More precisely, “.. maternity (of the cows in the context of the Gerzean rock art of Nubia)… was generalized to include ostriches.” (Ibidem) Thus, drawing on evidence from the Upper Egyptian Neolithic, links between the female deity, the female character of the cord in question and possibly, the female gender of the “child” can be established. Even when leaving aside the gender aspect of the “child” “…this complex association of female symbols constitutes a schema related to birth.” (Ibidem)

With the exception of the arms, which are extended outwards, the “child’s” body whose legs are shown as a single element, gives the impression of a wrapped mummy in an upright position. If this “mummy” had been depicted with an erect penis, the notion that the god Min had just been born would have been evoked. From the “child” a double line, considerably less elaborate than the umbilical cord, runs down to another horizontal line representing the sky (Note that the use of the sky-hieroglyph has been confirmed as far back as the end of the Predynastic period only. S. Schott: Hieroglyphen. Untersuchungen zum Ursprung der Schrift. Mainz 1950, p. 24), into which a rain emitting cloud is incorporated. (figures 13 -15)

figure 13: child-god, rain-god, two clouds, a pubic triangle and an ostrich; colour enhanced

figure 14: detail of the dim vertical double line connecting the child-god with the upper cloud

figure 15: detail showing the two rain emitting clouds; the lower one superimposed on an ostrich; colour enhanced

In the later Pharaonic period “rain or dew falling from the sky” (E.A.W. Budge, op. cit. p. CXXiV, No. 4) was represented by a hieroglyph (Ibidem) very similar to the prehistoric depictions of this meteorological event. At Djedefre´s Water Mountain, two depictions, both vaguely related to this Hieroglyphic sign (see expedition report 2005/6 on this website) and also to the rain cloud in question can be seen. (figures 16 +17)

figures 16 +17: 4th dynasty meteorological notations and K.P. Kuhlmann´s transcriptions

Below the rain emitting cloud there is yet another cloud which is superimposed on the image of an ostrich. (figure 18) There is also a pubic triangle on the left, almost connecting with this cloud, the connection serving as a roof-like “sky shelter” for a mysterious anthropoid figure. What is the meaning of this? A close look reveals that the enigmatic individual consists of a torso without arms on which a round head is mounted. The skirt like lower body lacks legs and feet which are replaced by a cluster of five vertical lines, enclosed on both sides by inward curved outlines. Doubtless, this odd figure which resembles a cloud itself, alludes to a rain-maker goddess. It is the rain giving deity herself! (figure 19)

figure 18: rain goddess below the “roof of the sky” the latter distorted by the image of an ostrich

figure 19: image of the rain goddess (close up)

To sum up, it may be ascertained that, in later times (when droughts had become a recurrent meteorological feature), the “child god” appears to have been established as a mediator between his parents, who are the pair of deities to his left and the composite deity or rain-maker goddess below him. The pictographic cluster consisting of pubic triangles, rain clouds, an ostrich and the rain-maker deity herself, may thus symbolize reproduction and female fertility or the urges connoted with it, during a period of infrequent rains at the end of the Neolithic Wet Phase as experienced in the Wadi Sura area. Hence, this cluster, its linkage to rainfall and to the “child god”, must have evolved out of a tangible need and therefore may have to be interpreted as a spell or a lamentation carved into the rock to prevent or to overcome human tragedies caused by absent or insufficient rainfalls. As the link between the “child god” and the upper rain-cloud is only faintly engraved, and as a “sky-extension” is superimposed onto the ostrich by means of the horizontal stroke that belongs to the lower cloud, it is likely that this link as well as the two clouds and the rain-maker goddess, were carved into the sandstone at a later date than the majority of the WG 21 rock art, possibly during a period of environmental stress. If this is true, such a notion would lead to the sound conjecture that, the rain goddess and her divine companions were considered as local deities by the Neolithic population of the Wadi Sura area. Furthermore (leaving aside for the moment the reddish brown coloured figure outfitted with a naturalistically shaped penis (see figure 9) which may be even of a later age, in order to concentrate on the other figures and their surroundings which are connected by the umbilical cord or by the double line), the nucleus of this family grouping which initially consisted of three deities, was extended when the Neolithic population of Wadi Sura became subjected to the pressures of climatic change. Thus from an existing triad of local gods it became a tetrad i.e., a group of four local gods. Looking in this way at this complex panel of prehistoric rock art, it becomes clear that these deities reveal a genealogy of the gods created in the desert that echoes the mythic symbolism of later Pharaonic times and that also gives insight into how and why these divine genealogies came into being.

There is yet more evidence to substantiate the notion that the rain-maker goddess image created by Neolithic people and interpreted by Le Quellec et al. as a medusa (J. Le Quellec, P. and P. de Flers: op. cit., p. 214, figure 599) was in fact intended to represent a deity proper. Her “rain skirt” consists all together of seven strokes. This “..is certainly not accidental, but it is constructed according to a system of cultural references that is now lost to us.” (B. Midant-Reynes: The prehistory of Egypt. Oxford 2000, p. 179) For comparison: eleven vertical strokes are attached to the upper rain cloud and twenty two to the lower one. What is the reason for the sparse use of strokes when it comes to the design of the deity’s skirt? Although it is somewhat speculative “…to extrapolate back from the (Pre-) Dynastic period into prehistory… (since) new myths are grafted onto old rites until almost all sense of their original identity has been erased” (Ibidem), some parallels should be drawn: On the Narmer macehead, the Narmer palette and also on the mace head of the Scorpion king, a symbolic element consisting of a rosette with seven petals can be seen. (See K. A. Bard: op. cit., pp. 298, 302, 303. Note also that Saad found a pendant in the form of a small wheel of green faience which he interpreted as palm tree with seven braches and a trunk and which he viewed as a representation of the goddess Seshat. Z.Y. Saad: The excavations at Helwan. Norman 1969, pp. 57, 59). In case of the Scorpion king the ruler’s name itself consists of such a rosette and the image of a scorpion. Although the political meaning of the three artefacts remains obscure, one may reason that the rosette itself as well as the number seven as evidenced in the rosette’s petals, possibly constituted a component of the king’s name. Hartung assigned a similar rosette found on a seal belonging to the tomb of U-j, to a high Pre-Pharaonic office involved in the control of long distance trade. In later times such trade became the sole privilege of Egyptian kings. (U. Hartung: Prädynastische Siegelabrollungen aus dem Friedhof U in Abydos (Umm el-Qaab). MDAIK 54 (1998), pp. 211, 213) Contesting Hartung´s interpretation that the Scorpion King’s rosette constitutes a part of the spelling of a rulers name, Baumgärtel argues that it is a symbol of a goddess. (E. J. Baumgärtel, in ZÄS 93 (1966) pp. 9 et. seq., cited from G. Dreyer: Ein Segel der frühzeitlichen Königmetropole von Abydos. MDAIK 43 (1987) p. 42) Leaving this aside we consider the idea of Dreyer who sees seven-petal-rosettes as an expression of (the king’s) divineness, thereby, partly reconciling both interpretations. Could this expression of divinity also apply to the number seven independently of the floristic motif? Venturing from the realm of probability into the realm of prudent speculation, I propose that the number seven could be considered as having been sacred in Neolithic times, imbued with a “religious” or ritual meaning, signifying the divine.

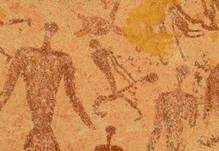

Side note: Aldred has pointed out that the Egyptian concept of the god-king derived from the “…prehistoric rainmaker who kept his tribe… (and their domestic animals) in good health by exercising a magic control over the weather... (who was)… transformed into the Pharaoh, able to sustain the entire nation by having command over the Nile flood.” (C. Aldred. The Egyptians. New York 1963, p. 157) Such a transformation cannot be inferred in the case of the WG 21 rock art as the depiction of a chieftain with a mace who just has smitten an enemy, (figure 20) whom Barta considers the prototype of the ancient Egyptian kings (M. Barta: Swimmers. op. cit., p. 6.) is seemingly not endowed with any rain-making qualities. Such qualification seems to rest solely on the rain-maker goddess to whom, in periods of drought, the Wadi Sura tribe may have performed sacrifices.

figure 20: prototype of the ancient Egyptian king smiting enemies

Although there is no evidence, neither from the Neolithic period nor from the Pharaonic as to what happened to the rainmaker-chieftains or kings during times of severe drought, we are informed about their fate in recent times and from various regions of Africa “… and there are anthropologists who believe that the ceremonial killing of the Pharaoh was sometimes revived in moments of crisis.” (C. Aldred: op. cit., p. 157) In the period between 8,500 – 5,000 B. C. serious droughts may have occurred more often in the area of the Gilf Kebir than the term “Neolithic Wet Phase” suggests as, according to Bolten and Bubenzer, the annual precipitation at that time did not exceed 100 mm. (A. Bolten, O. Bubenzer: Watershed analysis in the Western Desert of Egypt, in: Atlas. op. cit., p. 22) Bearing in mind the prevailing high evaporation rates during this period and the fact that the rains may have fallen only episodically or seasonally, water may not have been easily available all year round. However, the first stratigraphic evidence ever, recovered from a small settlement site in the area confirms that despite this difficulty, a semi-sedentary life at around 5,700 B.C. was possible for at least one hundred years in the Wadi Sura area, lying as it does, at conveniently close quarters to several palaeodrainage systems, thus suggesting this period to be the most likely one in which the bulk of the rock art of the region may have been created. (for details see part two of this report) With this in mind, we may conclude that it did not necessarily require the lasting desiccation that gradually set in around 5,300 B.C. (see R. Kuper, Environmental change and cultural history in northeastern and southwestern Africa, in: Atlas. op. cit. p.9), to cause people to call upon a rain-maker goddess. Such invocations might have been a frequent occurrence long before the onset of the period of dwindling rainfalls which, more than 2,000 years later, (beginning circa 3,000 – 2,000 B.C.) led to the creation of the hyperarid desert, devoid of vegetation, as we know it today.

Sehlis 4/13/2010

5. 32 Or is it a Triad (tetrad) evolving into a pentad? (corrected on 9/12/2010)

Rethinking the issue of the goddess depicted with her divine male consort by her left side (see figure 9 above), the composition suggests that:

- she has either just given birth to the small figure connected with her by an umbilical cord (figure 11) or she

- is related by kinship or lineage to this same small figure (in case of the latter the umbilical cord symbolising and expressing such an affiliation) in a way which may have been typical at the time (see preceding chapter).

Thus it may well be that the small rectangle above the head

- signifies that the personage is a female or

- signifies that the personage is a deity or

- signifies that the personage is both female and also a deity.

Thus, as Miroslav Barta has put it, we may see here not only, “… a rare combination of ´power and dominion´ (= mace) and fertility (= penis) so typical for later pharaohs” (M. Barta: pre-print, p. 92; initially Barta had envisioned the male figure as holding a mace in his right hand; a weapon I cannot discern), but also a combination of male and female fertility on an equal footing as well as a representation of lineage or kinship. (see similar view in F. A. Hassan: Primeval goddess to divine King. The mythogenesis of power in the early Egyptian state. op. cit., p. 312 et seq.).

Merging with my view that the engraved line connecting the female figure and the “child” is an umbilical cord, Barta subsequently states “Fertility cult and kin was of great importance even for the prehistoric populations in the Gilf Kebir – chieftain with a large penis in the Cave of the Beasts. He is followed by a woman with umbilical cord and with a child… This may be one of the oldest representations of a kinship.” (M. Barta, M. Frouz: Swimmers in the Sand. Dryada 2010, p. 96) If the figures in question are considered deities (as has been proposed in the preceding chapter), we may see here the nucleus of a family group that qualifies as a representation of a Triad of divine creatures who, (if the rain goddess is included in our considerations) developed later into a Tetrad.

But what about the “dressed individual” in figure 9 seen in the centre right, at the highest level of the composition (for a close-up see figure 21 below) who, like the male divinity to his right, is also holding his penis with the help of his (left) hand? This anthropoid figure is clearly not as closely connected with the other four deities as they seem to be with each other. His rather more detached status is evident by the fact that he is not attached to the umbilical cord or to any other engraved line, nor is he holding hands. He is superimposed onto an ostrich and the faint engraving of a quadruped´s legs. The skyline and the rain cloud (below the child god) that are also depicted, are also superimposed onto another ostrich. (see figures 13 + 15 above) These superimpositions indicate that the “dressed individual” is younger than the Triad thus, most probably, of the same age as the depictions of the clouds and the rain goddess.

figure 21: dressed individual with “unnaturally” erect and extraordinary large penis

figure 22: for comparison: naked hunter with flaccid penis (from WG 72)

Why does this enigmatic attired individual stand somehow lost in the scene? And why is his penis not fully erect (in contrast to the ithyphallic character to his right who boasts a fully erect member)? Seemingly, his penis, although sexually aroused and incredibly extended, is not in the normal upward pointing or horizontal angle you would expect in a fully erect penis (which, amongst other deities, later became a characteristic feature of the god Min) but instead is pointing down. Such a defective curvature can be hardly explained as a possible medical condition (of the penis) during an erection. However, could it be that we see here an old but still powerful man? Is this the reason why this individual is shown fully dressed (his attire is the only item in the scene bearing traces of reddish brown ochre paint) and why he is depicted with such a large penis? (Does he constitute a symbol which may represent the combined qualities “enduring might” and “old age”?) By contrast, figure 22 displays a naked predecessor of the “Libyan hunter” from a slightly later period wearing a feather on his head, his penis (not sexually aroused) depicted in a rather naturalistic state. The depictions provide credible evidence for the existence of refined artistic articulation that could, in a masterly manner, clearly differentiate between various kinds of sexual arousal.

A close look at figure 9 (an enlargement of which is presented in figure 23) reveals that, in contrast to the penis belonging to the male deity on the leftmost side of the penal, the penis of the “dressed figure” is clearly directed towards the “child”. This leftmost male deity together with his female consort, also seems to be walking leftwards and westwards (and/or is shown in a position that that is averted to the “child”), with the female following the male, thus, both are moving away from the “child”, whilst the “dressed personage” from his position in the scene, the orientation of his feet and featureless head (note that this head is positioned on the corpse slightly to the centre right), seems to be facing this “child”.

Why do “parents” of high social status abandon their “child”, even though this child is still connected by the umbilical cord with his mother? In my view, such conduct is not the natural behaviour one would expect from human beings which suggests (mythologically justified) that these are the actions of gods. As the “dressed anthropoid figure” is of younger age than the Triad, the fact that it was added to the scene at a later time could be indicative of a change in the mythology of the people concerned (or of an advancement to their “tales of the gods”) and it seems there had existed a need to make such a shift explicit in the rock art.

Does the depiction allegorize the outcome of a paternal quarrel; a fight in which both ithyphallic creatures were involved? Or, to phrase it more cautiously, had there existed an urge to make it retrospectively clear, who really was the father of the child god? Can we here envision the “dressed figure” as a god? Half way between this “dressed” god and the divine couple something has been obliterated. Would the missing depiction have given us additional insight into the interpretation of the scene?

figure 23: Enlarged detail of figure 9

To the best of my knowledge there are no accounts in Egyptian mythology/religion that resemble the tale that is being told in this panel (figure 23). Even the fight between Seth and Osiris, with the latter´s resurrection by Isis (see E.A. W. Budge: Egyptian religion – Egyptian ideas of the future life. London 1987, pp. 41 ff.) so that he could conceive an heir (Horus), would not seem to be conclusively related to the scene in question.

Sidenote1: Whilst I was photographing this rock art panel at Foggini´s cave, the ancient Greek myth of Sisyphus came to mind. It seemed to me that a revelation similar to the one that disclosed that Sisyphus was the father of Ulysses and not Laertes, was here being related. After Sisyphus (= dressed individual to the right) had seduced Antiblia (= the female on the left), she became pregnant and hastily married her fiance Laertes (= the male on the far left) thus, awarding the unearned joy of fatherhood of the child (= the small figure on the far right) to Laertes.

It had been assumed by Wilkinson (R. H. Wilkinson: The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt. op. cit., pp. 12-15, 20) that in pre-historic times gods in human form had emerged or developed more slowly than zoomorphic type deities. Similarly, Assmann states a “… preceding ´prepersonal´ phase in the history of Egyptian religion… (moulded) the classical form of Egyptian polytheism..” (Jan Assmann, The search for God in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca and London 2001, p.101) concluding that, with “.. the coming into being of the persons of deities – that is, with the personalizing and thus the anthropomorphizing of the Egyptian concept of the divine – polytheism came into being…” (ibidem) If here, we leave aside the issue of whether or not Egyptian religion originated from a stellar cult (see Report on the results of radiocarbon datings from the Wadi Sura area, Gilf Kebir, southwestern Egypt, attachment 1 – additional 14C-datings, sidenote 4), we may, for a moment, unquestioningly follow Assmann´s further conclusion that, as the “.. history of religion knows many forms of apersonal concepts and experiences of the numinous…(,) animal, plant, and fetish forms of many Egyptian deities point to a preanthropomorphic and thus probably also prepersonal phase of the form of the numinous.” (ibidem, p. 101 et seq.)

Indeed, until now, the evidence in the archaeological record from Nabta Playa in Egypt´s Western Desert confirms that the earliest worship of animals, believed to be gods in animal form, may have considerably preceded the creation of human type divine beings. Examples of such evidence are:

a.) offerings of domestic animals (dated to 5,900 – 5,500 BC; see M. Barta, M. Frouz. op. cit. p. 79),

b.) a regional ceremonial centre comprising cow and sheep burials at around 5,500 – 5,400 BC (Ibidem, p. 83)

c.) a carefully worked sandstone block which resembles an animal, most likely a cow, which also may reflect such a progression. (The sculpture cannot be dated but may be associated to the megaliths and tumuli believed to belong either to the period of 5,500 – 4,600 BC or to the interval of 4,500 – 3,100 BC.) (Ibidem, pp. 83 + 87)

However, the older, enigmatic type, pre-cattle pastoralist portion of the imagery at the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave (dated to around 6,000 – 5,600 BC) suggests that the tendency for animal deities to evolve faster than the human deities cannot be confirmed there because the depicted scenes include both the strange zoomorphic “headless beasts” and also the antropomorphic deities (shown in large scale) and human figures that surround them (pictured in small scale; see chapter…. below). Furthermore, the anthropomorphic divine Triad/Tetrad/Pentad engravings ie., the proposed birth scene discussed at length above and in chapter 5.31 which, most likely, are contemporaneous with the “headless beasts”, are portrayed without divine zoomorphic companions. Do we perhaps see here the oldest representations of gods in human form known so far in the Egyptian hemisphere?

Returning to the statements of Wilkinson and Assmann, if one accepts that this group of anthropoid figures depicted in the birth scene is indeed either a Triad/Tetrad/Pentad, it again weakens the proposal that the development of zoomorphic deities had considerably preceded the creation of gods in human form. At the same time, however, it strengthens the proposition that the Egyptian pantheon and religion partly originated in much earlier times from the Libyan Desert. In this case the birth scene would serve as further evidence which adds to the sparse and ambiguous records of gods in human form from early pre-dynastic Egypt, extending the earliest date of their creation further back into prehistory.

Carlo Bergmann

Sliema, Malta 8/13/2010

posted on this website 8/31/2010

5.33 More about sacred numbers

As a supplement to what has been outlined in chapter 5.31 above and in my “Report on the results of radiocarbon datings from the Wadi Sura area, Gilf Kebir, southwestern Egypt” (attachment 1, chapter 1.3) I would like to remind readers that in his book ´Symbol & magic in Egyptian art´ (London 1994), R. H. Wilkinson had written at length about the magical symbolism underlying Egyptian art and notably, in chapter 6 of his book (pages 126 – 147), the author focuses on the meaning and symbolism of numbers as understood by the ancient Egyptians. Can Wilkinson´s ideas also be applied to the Neolithic?

Desirable as it may be, I feel it is still too early to discuss the possible correspondences that may exist between Egyptian sacred numbers and their allied mythical-religious themes on the one hand and the rock art of the Western Desert cultures on the other. Notwithstanding my findings as described in chapter 5.31 and in my report on the radiocarbon datings from Wadi Sura, such a discussion would, at the moment be completely inconclusive on account of the sparseness of archaeological data covering this distant epoch that has accumulated so far. However, there is an entry in the Wikipedia website that attempts to set up a list of sacred “pharaonic numbers”. Although this list is partly wrong and so far lacking in sufficient citations which may verify the statements in there, the link concerned is quoted for the interest of readers. (http://en.wikepedia.org/wiki/Numbers_in_Egyptian-mythology):

- Number “3”: “..basic symbol for plurality… Triads of deities were also used in Egyptian religion to signify a complete system.”

- Number “5”: “It took five days for the five children of Nut to be born…. The star, or pentagram, representing the afterlife, has five points.”

- Number “7”: “Symbol of perfection, effectiveness, and completeness.”

(quotes from (http://en.wikepedia.org/wiki/Numbers_in_Egyptian-mythology)

BTW, in my opinion the comments on numbers 5 + 7 support the notion that the figure Le Quellec interpreted as a medusa (fig. 18 above) is indeed a goddess.

When time permits efforts will be made to delve deeper into the symbolism of numbers.

Carlo Bergmann

Sehlis 9/12/2010

5.34 Headless Beasts and the issue of the sky goddess Nut

5.341 Evidence of phallic cult practises

I am not surprised that the phallic cult reflected in the birth scene, discussed at length in chapters 5.31 and 5.32, reappears, albeit in modified form, in other sections of the spectacular rock painting that embellishes the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave (WG 21). Three scenes where the existence of such a cult are indicated are listed below. (Phallic cult practices were not confined to the Wadi Sura area only. This is proved by the large sandstone sculpture of a penis found at Gebel Uweinat. See figure 3 above.)

- Figure 24 shows persons in a “…strange unnatural semi-squatting body posture (legs apart, and knees at right angle)…” (A. Zboray: Rock art of the Libyan Desert. 2nd expanded edition. Newbury 2009, Rock art styles, Wadi Sora style). From the pelvis of one of these figures rises a large phallus. The phalli of the individuals to the left and right of this figure apparently have been obliterated.

- Figure 25 displays a male individual in a similar semi-squatting body posture holding his member with both hands. His phallus is very similar to the ones shown in the birth scene. Such similarity makes it clear that the body part in question is indeed a penis and not a tool or a weapon. There are three individuals in an upright position standing next to the ithyphallic figure as though they were his audience.

- In figure 26 nine ithyphallic individuals are lined up in single file.

figure 24: male figure in a semi-squatting body posture holding his erect penis with one hand

figure 25: another figure in a semi-squatting body posture holding his erect penis with both hands

figure 26: nine ithyphallic figures walking in single file

Sidenote 2: There are other scenes at the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave that possibly could be depicting phallic rituals but it is not certain that these images are phallic in nature. See for instance the hostile(?) scene depicted in figure 27 where combatants(?) seem to be wielding slightly kinked tridents that are supported from the lumbar or hip region of these fighters/dancers. Although the meaning of this imagery is obscure, the manner in which the spears are being held does resemble the way in which the erect phalli are being held in figures 24 – 26.

In the case of the warriors(?) shown in figure 28, the question of whether or not the figure in the lower left of the scene is lifting his mace or is holding his erect penis, is not easy to answer. As this particular combatant is depicted in a vigorous forward striding posture, it seems unlikely that, the Neolithic artists intended him to be the only one in the scene with an erect penis. Thus, this possible phallus might just as well be a mace handle with a stone mace fixed to its tip.

figure 27: hostile scene showing archers (right) and a group of figures (left)

lifting slightly kinked tridents(?)

figure 28: warriors(?) lifting their maces

These examples may suffice to convey the uncertainties which we face when trying to interpret seemingly insignificant but, for the purpose of analysis, important scene elements of the WG 21 rock art. Against this backdrop and even though these men are holding their arms in a position untypical of such an activity, it comes as no surprise that Barta interprets the cluster of ithyphallic individuals shown in figure 26 as offering bearers (M. Barta, M. Frouz: Swimmers, pp. 41 + 51). (The standard Old Kingdom body posture of offering bearers is shown in figure 20 of Barta´s “Swimmers”. Two engraved human figures in a kneeling posture which are interpreted as copies of the offering bearer of the Mentuhotep II inscription by Zboray and Borda, were found in the immediate vicinity of the inscription at Gebel Uweinat. See A. Zboray, M. Borda: Some recent results of the survey of Jebel Uweinat. Sahara 21(2010)p. 188) Let´s now return without further ado, to figure 26 and try to unravel the details of its interpretation.

5.342 Barta´s “white Nut” surrounded by gods

The composition is part of an enigmatic scene (figure 29) in which, as Barta sees it “…a large figure of a composite body painted white… leaning against the ground in a way similar to later depictions of the goddess Nut in ancient Egypt…”, is brought together with “.. a red figure of a male (the earth god Geb), which seems to support her body, reclining on his right elbow and with his left arm touching/supporting her breast. His legs are unnaturally long and nine men are depicted walking on them from the right side. In their hands they carry large, elongated items resembling joints of meat brought by later offering-bearers as attested in Egyptian tombs from the Old Kingdom… The assumed offering bearers may refer to ancient inhabitants of the desert who were ascending from the desert plateau to the cave which was considered a place of transition. In the cave were meeting the profane world with the netherworld. And thus the cave was the place of their interference as was the goddess Nut.” (M. Barta, M. Frouz: Swimmers, pp. 41 + 51)

Barta then continues: “The scene is complemented by two more, large and thin figures of gods, one to the left of the White Goddess and another one below her trunk, with both arms outstretched to her breast. They are also the two gods, known later in ancient Egypt as Shu and Tefnut. Two considerably smaller human figures complement the scene on the right and another pair of human figures (male ones?) is shown just in the place of the missing head of the goddess. They appear to venerate her.” (Ibidem)

figure 29: Neolithic precursors of the sky goddess Nut, the earth god Geb,

Shu and Tefnet approached by nine men. Note the hostile scene in the

lower left of which an enlargement is shown in figure 28.

5.343 Can the Wadi Sura rock art be linked with the cultural development in the Nile valley?

We had reached the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave at noon on December 12, 2009. Whilst my friends took their well deserved opulent lunch at our camp site, a couple of kilometers south of WG 21, I was lucky enough to spend a few hours alone admiring what has been rightly qualified by Andras Zboray as “…the most important rock art site in all of the eastern part of the Sahara.” (A. Zboray: op. cit., no page numbers) As time - spent in solitude - passed, a feeling evoked in me the vision that I had arrived at the origin of the Egyptian religion. In the Nile valley this religion and the conception of its gods and goddesses reveal themselves mainly in texts: in the writings of the early sages of Egypt, in hymns and epithets. At WG 21 there was silence. But even this silence seemed to be absorbed by the presence of the magnificent, rather abstract and highly symbolic-religious rock art. I felt this extreme void. I felt that I had entered a holy site, a place of rituals and worship bare of utilitarian use. I had stepped into a temple.

But where were the altars? If Egyptian religion is a product of different periods “… so remote that it is useless to attempt to measure by years the interval of time which has elapsed since it grew up and established itself in the minds of men…” (E.A. Wallis Budge: Egyptian religion. New York 2005, p. 2), one should also note that “of the gods of the prehistoric man we know nothing, but it is more than probable that some of the gods who were worshipped in dynastic times represent, in a modified form, the deities of the savage, or semi-savage, Egyptian (outside the Nile valley; S. Morenz: Egyptian religion. Ithaca, New York 1992, p. 233) that held their influence on his mind longest.” (E. A. Wallis Budge, 2005, p.86) Thus, could some of the threads for unveiling the roots of the Egyptian pantheon be picked up here?

Rock art specialists like Andras Zboray argue that, most “.. of us studying.. (Wadi Sura rock art) have their knowledge base firmly rooted in the Egyptian civilization, and often look for analogies there.” (email of 9/16/2010) Thus, it is this background that “…introduces a cognitive bias. We try to explain things using an Egyptian frame of reference and terminology, often ignoring the far more overwhelming evidence from Saharan rock art.” (email of 9/26/2010) In addition, emphasizing that “…the Gilf/Uweinat cultures are linked to the broader Saharan-Sahelian cultures, and have no link whatsoever with the Nile valley”, Andras points out that “there is a time gap of at least 3,000 – 4,000 years between Wadi Sura and the time the Road to Yam and Tekhebet was in use.” (email of 3/25/2010) Therefore “.. one should not draw conclusions from single isolated examples without consulting the broader picture.” (email of 9/15/2010)

My perception regarding the permeability of the Western Desert during the periods in question is different. To me, cultural contacts with areas to the east of the Gilf Kebir during the said periods are as likely as contacts with the Saharan-Sahelian cultural sphere. (see also sidenotes 2 + 4 of my “Report on the results of radiocarbon datings from the Wadi Sura area, Gilf Kebir” on this website.) How, otherwise, can it be explained that, around 2,000 BC, when climatic conditions had worsened, donkey caravans were able to move along the Kufra Trail, from Wadi Sura to Dakhla oasis and vice versa, without the need of an elaborate water supply system? On this trail each of the ancient water dumps comprises, if any, of no more than two water jars. Certainly not enough storage facility for thirsty caravans thus, implying that water, food and feed were permanently collected from the surroundings of the trail. (Hopefully, my report on the Kufra Trail will be published next year on this website)

Sidenote 3: By the way, a TL-date from a pot sherd found at WG 49 revealed an age of 4,700 +/- 20% (circa 3,600 – 1,800 BC) indicating that during the period in which the Kufra Trail was in use, the Wadi Sura area still may have been regularly inhabited. (On the inaccuracies of the TL-dating method see my remarks in previous reports on this website.)

Sidenote 4: For the camel period, Harding King reports a convincing case of a wandering existence in the Sahara. Before the introduction of motor vehicles to the desert Haggi Qwatin Mohammed Said, one of his guides and “… a native of Surk in Kufra Oasis,…had acted as a tax collector among the Bedayat for Ali Dinar… He had a Bedayat wife in Darfur, a Tawarek one somewhere near Timbuktu and one if not two others near Manfalut … The last time he was in Farafra… he was on his way back from Tibesti … Quaytin´s knowledge of the least known parts of North and Central Africa was profound… He gave me enough data to form a fairly complete map of the unknown portions of the Libyan Desert, with a great deal of the Bedayat country and Endi… The map when completed contained the names of some seventy places that… had not previously been recorded; many of them have been found since, approximately in the position in which they were shown. (W. J. Harding King: Mysteries of the Libyan Desert. London 2003, pp. 199, 207, 210 et seq.)

Even long before, during the “… climatic optimum, the Eastern Sahara was far from being a paradise. The amount of annual rainfall, estimated to a maximum of 100 mm during the Holocene humid phase… or slightly higher in mountainous regions, such as the Gilf Kebir… indicate a dry savannah with episodic rains and a patchy and unpredictable availability of surface water and related resources such as vegetation and wild animals. These factors created living conditions of high risk and stress for the foragers of the Eastern Sahara. Highly variable spatial and temporal logistical and residential mobility patterns are likely to be adaptive expressions of risk minimization in the Western Desert.” (H. Riemer: Prehistoric rock art research in the Western Desert of Egypt. Archeo-Nil 19(2009) pp. 34 et seq.) Were highly mobile Neolithic tribes that frequented the Gilf Kebir, as mobile as the much later pharaonic donkey caravans? I think so. These tribes must have been able to traverse hundreds of kilometres of what we consider barren lands. By adapting to their environment and to seasonal rainfall which, in those early times, may have been much more predictable than during the dynastic period, tribal groups practiced a wandering existence and may have managed to go wherever they needed to travel. Only fear of their foes prevented them from doing so. Thus, taking into consideration the permeability of the desert-steppe/dry savannah as described above: why should there not have existed, in the Neolithic period, an “open door” also to the Nile valley?

Why not, for now, accept Budge´s aforementioned vision and Siegfried Morenz´ fascinating thesis put forth in 1960, according to which in “… the early period… the Libyans to the West played a significant role … in the development of Egyptian culture … (so that their) influences should not be accounted as foreign borrowings… (but rather as) an integral part of the process whereby the Egyptians constructed their own cultural forms”? (S. Morenz: op. cit, p. 233) Why not follow Barta´s remarkable approach to the splendor of WG 21 and WG 52 as outlined in his “Swimmers in the Sand”, which may lead to a paradigm shift with regard to the way we view and interpret the Wadi Sura rock art?

Sidenote 5: With once´s naked eye the careful observer will notice that some of the XX WG 21 images may have been deliberately(?) washed X whilst others were overpainted XX up to at least five times XX. Considering these omnipresent X superimpositions and bearing in mind that probably, XX half of the WG 21 rock art was still covered by sand when we XX visited the cave, the estimated XX number of its depictions XX may run into the thousands. Thus, with regard to the number of paintings, the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave may not only be the biggest rock art site of the Sahara but perhaps, also of the whole world.

The overpaintings XX considerably complicate rock art analysis for those to whom XX advanced image enhancement is not available. Because of lack of such techniques my study will focus on what can be clearly X seen with bare eyes.

(sidenote corrected on 11/21/2010)

5.344 The procession of nine ithyphallic figures symbolizing earth based X fertility and strength

Looking at the complex composition shown in figures 29 + 31 whilst at the same time, focusing on Barta´s “assumed offering bearers” (shown in the lower left of figures 29 + 31 and, as a detail, in figure 26), a slightly different interpretation of the scene entered my mind as follows: With regard to the two large, standing figures arched by the white body of what, subsequently, may have become the sky goddess Nut, the figure on the right may foreshadow the Egyptian air god Shu and the figure to his left, resting the handless tip of his arm (not his right elbow as Barta sees it. Because what may be interpreted as Geb´s forearm is, in fact, a floating figure. See figure 30.) on one of Nut´s legs, may be an early form of Geb, the Egyptian earth god. In Egyptian mythology Geb is occasionally depicted with an erect penis. (see for instance, W. Forman; S. Quirke: Hieriglyphs and the Afterlife in ancient Egypt. Norman 1996, p. 9) Would therefore, the procession of ithyphallic figures shown as if they are just about to ascend Geb´s legs, symbolize the attribute of male fertility? Note that there is a striking iconographic similarity between the Neolithic and the dynastic representation of Geb when, X to emphasize his fertile nature XX, in the 21st dynasty, the god´s body was portrayed with a covering of the hieroglyphs for ´reed XX. (R. H. Wilkinson; op. cit., p. 106)

figure 30: floating figure close to the tip of Geb´s arm and to Nut´s leg

Sidenote 6: For the sake of promoting open discussion I want to acquaint the reader with a fundamental objection put forth by Andras Zboray. In his email of 9/26/2010 Andras writes: “This whole argument relating Geb is an excellent illustration of what I call “cognitive bias”. An isolated element is taken from the Egyptian pantheon, and compared to an isolated element of the paintings, noting some very real similarities. However the implied conclusion is in my opinion incorrect, as only the apparent similarities are included, ignoring 99% of the remaining corpus of paintings where no such similarity may be established. What you write is technically correct, but cannot be accepted by itself as evidence for any cultural links.” At this stage, it may suffice to reply that, cultural differentiation as evidenced in the WG 21 rock art, would not at once have started on a broad scale but rather, it began with a new perception of the world followed by a search for alternative means of religious and artistic expression. At the beginning of such a transformation within one and the same culture only tiny, fragmentary and unspectacular changes in expression may be noted before, much later, a separation and an autonomous development of new cultural, religious and artistic traits took place. However, as long as such a process had not matured, “old” and “new” means of expression may have coexisted and interoperated within the same cultural context.

BTW, nowhere in the world, there exists a cultural or an art concept that saw the light of the day in fully developed form. This was true for the hieroglyphic writing system. And it also may have been the case with regard to the evolution of the Egyptian pantheon and the Wadi Sura rock art.

Furthermore, neither Barta nor myself do compare “isolated elements”. Instead, what we do is to compare key themes of the WG 21 imagery with the religious and power iconography of the Nile valley both of which exhibit striking iconographic similarities thus, suggesting mythological analogies. Our interest focuses on themes and not on depictions of a matchstick man here and an ostrich or a headless beast there. In my view, there are indeed complex conceptual analogies which hint at a cultural link between the Gilf Kebir and the Nile valley. This issue cannot be decided by the argument that, on the whole, (and by counting figures, “isolated elements” or motifs) statistical likelihood is against such a cultural connection. Note also that Kupers team so far, verified interregional contacts between the Gilf Kebir and southern Egypt, reconstructed on the basis of stone tool production, for the time around 8,300 BC and for the period between 6,800 and 4,300 BC. (See my Report on the results of radiocarbon datings from the Wadi Sura area, Gilf Kebir on this website. ) In addition, Wendorf and Schild “…discovered many indications that there might be a strong connection between the Sahara Neolithic and the Neolithic in Upper Egypt..” (M. Barta, M. Frouz: op. cit., p. 77) thus closing the remaining geographical gap between Nabta Playa and the Nile valley. It is most unlikely that, even later, these interregional contacts were limited to the transfer of handicrafts and did not comprise religious and cultural ideas. Andras and other authors have characterized the unique WG 21 imagery as a very specific piece of rock art. The fact that some of its iconography bears resemblance with the religious and power imagery in the Nile valley can hardly be a coincidence.

At WG 21 the symbols of fertility as represented by the nine small phallic creatures, are not assigned to the god´s lumbar area but instead, to his lower limbs. Geb´s legs are shown as being extremely long and footless, giving them the appearance of the roots of plants. Were these root-like legs and the cluster of ithyphallic figures an artistic means of expressing the divine fertility of the soil by the Neolithic painters? Hence, is it the intention of the painting to disclose to the viewer, the age old message that the strength of every organism living on land is derived from the soil (and from the breasts/penis which Geb is touching with his left hand)? From this point of view, fertility and power as qualities of the earth “emanate ” from the ground through the mediation of Geb who, by his mere presence, may have transmitted these two important properties of fertility and power to the inhabitants of the Wadi Sura area.

Apparently, at the time when the mythical-religious scenes at WG 21 were created, sophisticated artistic means of depicting the divine, in particular, the ability to conceptualize earth based X fertility and power, did not exist. Thus, it seems that an already prevailing phallus cult was slightly modified so as to represent the “emanation” of the earth´s attributes. Consequently, Geb is not depicted with a large phallus in the region of his pelvis but instead he is shown cohabiting with a number of small autonomous phallic characters painted further down on his body. These phallic figures are walking up his legs in single file and, so to speak, in a small and steady stream of finite doses (of power). Thus, in a simplistic way, the idea is being conveyed of a flowing of power that may invigorate people, similar to the minerals and nutriments that flow up from the roots in the earth to the branches of a tree.

Obviously, the Wadi Sura artists XX envisioned Geb (who represented earth based fertility and power) not in X a reclining position X but X as acting and upright standing XX. (To these X artists floating figures or figures rendered upside down seem to have represented the deceased. See M. Barta, M. Frouz: op. cit., p. 41) By means of the phallic procession along the god´s legs, a feature assigned to Geb alone, these early artists succeeded in pictorially distinguishing between Geb and Shu. Later in Egyptian history it became increasingly common to depict Geb in a reclined posture X. Conceptualizing him XX in that X way and featuring him with greater anthropomorphic detail from then on, Geb, as attested by numerous religious texts, was perceived as the bearer of the aforementioned qualities (earth based fertility and power). Furthermore, the god was associated with other attributes assigned to him at different times according to changing mythological needs. (see R. H. Wilkinson; op. cit., pp. 105 + 106)

(This chapter´s text corrections - in blue - of 11/21/2010)

But what about Nut? Lets look more closely at her body painted in “…unique white color… (which) allows for the possibility that at this early stage she was already considered to be an anthropomorphic form of the Milky Way.” (M. Barta, M. Frouz: op. cit., p. 51)

figure 31: color enhanced version of figure 33 (courtesy of Roland Keller)

Carlo Bergmann

Sehlis 9/28/2010

5.345 The “White Nut”: nothing else than a headless beast

When dealing with the large composite figure painted in white at WG21 which Barta considers “one of the most important scenes…” there (M. Barta; M. Frouz: op. cit., p. 41), namely, that figure that resembles the sky goddess Nut, the author emphasizes four major stylistic qualities or particular parts of the scene in question which may indicate possible mythical-religious correspondences between the cultures of the Neolithic Gilf Kebir and the Pharaonic Nile valley. These are:

a.) The “unique white color “ of the Nut-like figure which makes way “for the possibility that at this early stage she was already considered to be an anthropomorphic form of the Milky Way, which in ancient Egypt was associated with the legend of the birth of the sun god Ra.” (Ibidem, p. 51)

b.) The large size of the Nut-like figure which consist of “…a mixture of a beast’s legs and a female torso with a clearly visible breast.” (Ibidem, pp. 41, 51) The beast itself seems to resemble a panther. (Ibidem, p 41)

c.) “The figure is leaning against the ground in a way similar to later depictions of the goddess Nut in ancient Egypt…. Her head “… is missing and one can recognize only the neck” (Ibidem, p. 51)

d.) This “.. white goddess…” (Ibidem) is surrounded by three gods known from the Egyptian pantheon. These gods are Geb, Shu and Tefnu. (Ibidem)

Not everyone agrees that some of the scenes at WG21 are direct antecedents of later Pharaonic imagery and symbolism. For example Andras Zboray points out that in certain quarters, researchers have developed an unfounded cognitive bias (see sidenote 6) which, among other things, results in a preoccupation that leads some Egyptologists to search “…for Egyptian influence everywhere” (email of 3/25/2010.) To impartially assess the different views, one has to painstakingly focus on the facts as they come to light at the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave. Let’s therefore, take a close look at the stylistic features and scenes listed above, starting with the question of whether or not, the representation of a figure painted in “unique white” (which Barta considers to be a precursor of the sky goddess Nut) is truly peculiar amongst the WG21 imagery.

5.345.1 No indication for Nut being painted in unique white color

To the casual observer as well as to the rock art specialist, the color range of the Wadi Sura rock art at WG 21, “… is limited to “…basic red, white and yellow colors..” (A. Zboray: Rock art styles. Wadi Sura style. op. cit.). Most probably, this choice of colors depended on the range of pigments available and seemingly, no specific symbolic meaning was attached to any of these colors by the Neolithic painters. (see further remarks in chapter 5.345.2)

Sidenote 7: In his email to me of 9/22/2010 Andras Zboray wrote that during their visit to WG21 in 2003, Jean Loic le Quellec had found a small piece of yellow ochre in the ancient inhabited area at the foot of the WG21 hill. This piece of ochre showed clear signs of use thus indicating a possible link to the paintings in the cave above.

By contrast, in ancient Egyptian art “… the color of an object was regarded … as an integral part of its nature or being, just as a man’s shadow was viewed as part of his total personality… this is why the colors used in Egyptian art so frequently make a symbolic statement, identifying and defining the essential nature of that which is portrayed in a way that complements and expands upon the basic information imparted by the artist in line and form.” (R. H. Wilkinson: Symbol & magic in Egyptian art. London 1994, p. 104) Thus, “it is true to say… that wherever symbolism enters into Egyptian art, the use of color is likely to be significant.” (Ibidem, p. 105) Regarding the color white, ancient Egyptians associated it with cleanliness, ritual purity, and sacredness “…so it was the color of the clothes worn by ritual specialists. The notion of purity may have underlain the use of white calcite for temple floors. The word ´hd´ also meant the metal ´silver´, and it could incorporate the notion of ´light´ thus the sun was said to ´whiten´ the land at dawn.” (G. Robins: Color symbolism, in: The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt, vol.1, Cairo 2001, p. 291) Furthermore, Wilkinson points out that white was “…used with gold to symbolize the moon and sun respectively.” (R. H. Wilkinson: Symbol & magic. op cit., p. 109) This color was interchangeable with yellow/gold and therefore took on the symbolic meanings of these colors that, in the minds of the ancient Egyptians, were associated with what was eternal and imperishable. “The flesh of the gods were held to be of pure gold, and …(their bones) were said to be of silver…. The two-dimensional representations of deities are also often given yellow skin tones to reflect the mythological golden nature of their bodies” (Ibidem, pp. 84, 108) In Wilkinson’s view the associative link between yellow/gold and white is established by ´white gold´ (the mixture of gold and silver called electrum) which, in ancient Egypt “… was often regarded as being the equal of pure gold… Many sacred animals were also of.. (white) color, including the ´Great White´ (baboon), the white ox, white cow, and white hippopotamus.” (Ibidem, p. 108 et seq.)

But does this imply that the symbolic meaning regarding the coloration of Nut which Egyptologists identified in mortuary contexts where, (in dynastic times, namely) “…in the reign of Seti I and Ramesses IV,…the sky goddess… is depicted … (as a) celestial cow,… her body painted black or yellow as the night sky and covered with yellow stars…” (M. Barta, F. Frouz; op. cit., p. 57), held any significance for Barta´s white Nut-like figure or for the Wadi Sura Neolithic culture as a whole?

Sidenote 8: Discussing a depiction of Ramesses III before the gods (Harris Papyrus, British Museum, London), Wilkinson emphasizes that “…the king’s skin, which would normally be painted red if he were alive or golden yellow – as a god – if he were deceased, is not yellow but white. The two colors (yellow and white) are used in this way because of their essential equivalence… though the use of white skin coloration is less common.” (R. H. Wilkinson: Symbol & magic. op cit., p. 121) Applying Wilkinson’s reasoning to the Wadi Sura rock art: does this mean that Barta´s “White Nut” was painted white in order to indicate her divine status?

Judging from numerous WG21 rock paintings found above the sand during our visit, white seemingly, was not used to depict anything special, and there are, so far, no indications that a specific symbolic value is associated with it. This is substantiated by a number of scenes that show that apart from “Nut”, white was also used to depict human figures of different shapes and size, animals and other complex compositions that echo no specific color symbolism. (figures 32 – 38)

figures 32 + 33: White quadruped shown in original coloration and in a color enhanced version. The hind end of

the animal is supported by a pair of white hands/forearms.

figures 34 + 35: white feline(?) shown in original coloration and in a color enhanced version (courtesy of

Andras Zboray)

f

f

figure 36: white quadruped and white accessories on human figure to the right

(courtesy of Andras Zboray; color enhanced)

figure 37: white quadruped superimposed onto a reddish-brown human figure

standing next to a headless beast that is about to devour a human

(color enhanced)

figure 38: white quadrupeds and human figures lined up above a

headless beast (courtesy of Andras Zboray; color enhanced)

If a color preference at WG21 had ever existed, it was obviously that of red or reddish brown. But it must be accepted that even red may have had no specific significance because, as in the case with white, it was indiscriminately used.

Sidenote 9: In ancient Egyptian art red and yellow-white were used for gender differentiation and reflected “…at least to some degree ...the traditional outdoor/indoor roles of the male and female in Egyptian society.” (Ibidem, p. 10) Thus “… red was used to present the normal skin tone of the Egyptian male without any negative connotation (Ibidem, p. 107)… in contrast to the paler skin tone of the woman.” (Ibidem, p. 115) However, in the Wadi Sura rock art, “reddish-brown” was used indiscriminately to depict males and females, most probably signifying that there existed no difference in life style between the sexes in pre-dynastic gather-hunter and cattle herder societies as, in those times, life was more or less outdoor based for both genders. In this sense, the reddish-brown color is naturalistic as it seems to be based on objective reality, ie., on the actual skin color of the people of those times.

In comparison with the abundant use of reddish-brown in the Wadi Sura rock art, white and yellow are colors that were sparsely applied by the Neolithic artists. The meaning of these color preferences may never be fully understood. All that can be said at this stage about this restriction is that, in all certainty, it can be ruled out that such a sparing use of white and yellow was the result of convention.

Thus, based on the present evidence regarding the coloration at the Foggini-Mestekawi Cave, it is still too early to make comparisons as Barta does, and to draw conclusions about perceived similarities between the Egyptian sky goddess Nut as a manifestation of an anthropomorphic form of the Milky Way and the headless figure painted in white at WG21, which Andras Zboray, plain and simple, interprets as just another headless beast. At any rate, Andras´ view seems to be supported by the facts as they come to light with regard to “line and form” in the color enhanced version of the “White Nut scene” shown in figure 31 above.

Carlo Bergmann

Sehlis 11/21/2010

Sidenote

10:

Examining more closely the corpus of photographs of the Wadi Sura rock art

compiled by Andras Zboray

(A. Zboray: Rock art of the Libyan Desert. op. cit.),

one will notice further depictions of human and/or animal figures painted in

white. A few of the scenes containing such depictions from the

Foggini-Mestekawi cave and other rock shelters in its surroundings are

briefly discussed here. Comments and attempts to interpret choices of color

are included in the captions. Will this analysis provide answers as to why

the color white was used and did this color perhaps have symbolic

significance; at least in some of the paintings? It seems that the more such

scenes are investigated, the more obscure any symbolism they contain

appears. In the case of the ancient Egyptian culture, color symbolism is,

according to Wilkinson, amongst other things, “…usually an expression of

underlying religious beliefs which gave …

(a piece of art)

life, meaning, and power

(R. H. Wilkinson: Symbol & magic. op. cit., p. 8).

In the case of the Wadi Sura imagery, could it be that the juxtaposition or

interchange of certain colors is purely based on stylistic considerations?

The conception of

reality (German:

Wirklichkeitskonzeption) is greatly influenced by

colors. How colors are perceived, accepted, assimilated, “consumed” and

interpreted as part of the physical space that surrounds people may express

itself also in the Wadi Sura imagery.

(At present, unlike in Neolithic times, our conception of

the physical reality consists to a large

extent of prefabricated experiences.) In this

context an enigmatic relevancy, at least in parts, seems to be attached to

the color white. At

WG 21 for instance, a mythical creature, the

“white Nut”, and her surrounding world of images, whose intrinsic symbolism

may refer to a religious world in which the living exist alongside the dead

(Note that, for the